![]()

![]()

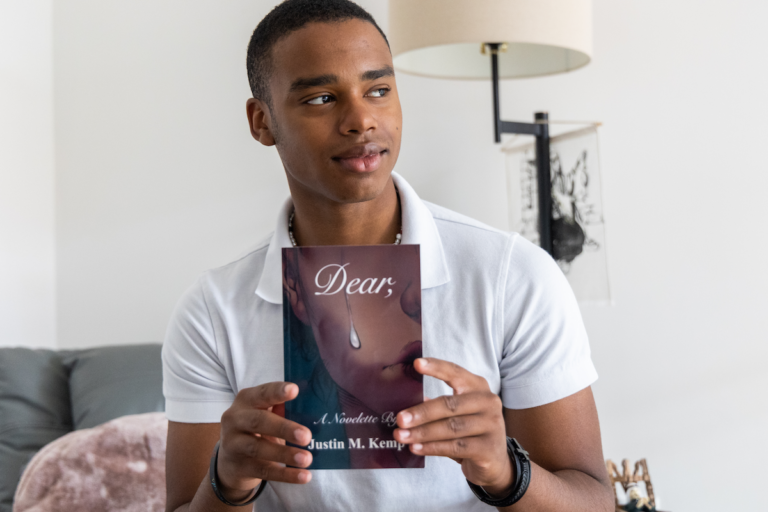

In his new book, “Dear,” Justin Kemp writes about minority teens facing mental health issues and opens up about his own struggles.

Listen 7:42

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

For a majority of his life, Justin Kemp has kept his emotions and personal struggles to himself.

Kemp, 17, is entering his senior year at Germantown Academy, near Philadelphia, where he’s active in student government and the Black Student Alliance. He also has aspirations to go to a historically Black university to study political science.

He’s a studious and insightful young adult that’s had academic success and a supportive family network. But mental health has played an important role in shaping some early childhood adversity.

In a recent book he published called “Dear,” Kemp opens up about his struggles with mental health, suicidal thoughts, and how writing saved his life.

The 90-page novelette features four teen, minority characters who are facing mental health issues of their own, and how social media, racial violence, and school shape teen mental health.

“This book is written for teens to resonate with and to know that they’re not alone, but for adults to also understand the pressures that the world puts on teenagers,” Kemp said.

The book also features something deeply personal to Kemp — his own suicide notes.

It was seven years ago when Kemp noticed something different about his moods and behaviors.

He was feeling more sad and depressed than usual. He was sleeping longer than he normally did, and inexplicably, couldn’t find the motivation to simply get out of bed.

“ I had never really heard much about mental health and the negative effects, so I didn’t think anything was wrong,” he said. “I was just a normal kid who was tired all the time.”

He never thought that poor mental health was the culprit, and felt too young to fully understand. But everything was far from normal. He began to develop a sporadic and inconsistent appetite. He would lose his cravings to eat for days.

“I was getting thinner,” he said. “I wasn’t eating at all. I can remember back a couple of years ago, I didn’t get out of bed for a week and I didn’t eat anything.”

Since Kemp was 10 years old, he has struggled with mental health in ways that have been difficult to overcome. Anxiety, in particular, began during middle school.

“Let me tell you, anxiety is the worst thing I have ever experienced in my life,” Kemp said.

What triggered his anxiety was feeling “forced” into crowded spaces like his classrooms. His emotions were usually followed by anxiety attacks. And he spent many school days going running into the bathroom in between classes to hyperventilate.

“I would have to go into the bathroom and just cry my eyes out before I could go and step in a classroom,” he said. “I did it because I didn’t know what else to do.”

Then, shortly after he turned 13, his mother and father – both practicing veterinarians in the Philadelphia area — got a divorce. For Justin, this marked a pivotal moment that took his struggles to an even darker place — looking for ways to end his life.

“I had gotten to the point where I would carry a bottle of Robitussin in my bag in case things had gotten so bad that I wanted to die,” he said. “That’s how dark it got. It was terrifying.”

Justin also began to take pills and cut himself. All he kept thinking about was how he “didn’t want to be around” anymore. He then started writing good-bye letters — or suicide notes — to himself and his parents:

Dear whoever is left to listen to me,

When I think back, I can remember myself sitting around a big boardroom table and shaking with the feeling of butterflies in my stomach. I can see myself in the grocery store standing in an aisle alone, scared that I might not make it home. I can relive that moment that I walked into the gym feeling no motivation to move. But the fact that the only reason I was there is because some guy on TikTok told me to get my ass up to work. I can see that time at Thanksgiving when all of my family had arrived and I couldn’t work up the strength to put on a smile. I can remember that it wasn’t because I wasn’t happy I could see them, but that I was tired of constantly being in pain.

Justin said he was very good at ‘hiding everything.’ No one at school knew about his emotional or behavioral health, so his suicide attempts mostly went unchecked, and he was never sent to the hospital.

Because his parents were in the middle of divorcing, they didn’t know what was happening either. That was until Kemp started seeing a family therapist.

“I actually started getting help when my parents got a divorce, and we started out by talking about my family situation,” he said.

![]()

Subscribe to The Pulse

Stories about the people and places at the heart of health and science.

Initially, he hid a lot of details about his mental health, but as time moved on, he felt comfortable enough to share more. His parents finally found out, too.

“And I’d say within about a year, I was able to actually open up about how bad I was struggling mentally. That’s how I actually got help,” Kemp said.

His therapist suggested that he should take antidepressants, which his parents did not agree with at first. He later convinced them that taking medication was what was best for him.

“My parents didn’t understand because they’re doctors and they know side effects and things like that. So they get cautious about things like that. It was a challenge,” he said.

During that time, writing became a form of therapy. It gave Kemp an outlet to talk about his mental health, and with the combination of medication, he felt more empowered to stay resilient.

He wrote notes to his parents, his cousins, and his friends. In “Dear,” Justin writes about how his suicide notes became a coping mechanism for his mental health, with reminders of how much he was loved.

My favorite memory is when I broke my arm in the eighth grade and we spent the whole day in the emergency room. The emergency room was horrible because they had to relocate my dislocated arm. But it was the night that brought about the memories that I will remember forever, thanks to you. I remember when we left. You bought me some candy from the grocery store. When we got home, you let me sleep in your bed. That was super comfy because you just put a cozy mattress pad on. You worked around the clock to make sure I was healthy and safe. That night, we watched movies together and I felt complete joy and safety. I just want to thank you for making me feel that so very often.

Kemp put a lot of thought and detail into describing silver linings in his book. He wants to remain an advocate for teens who struggle with mental health issues.

“I think that’s what was therapeutic to me,” Kemp said, “Understanding that I did have good moments and that I can still have better moments. And that’s what really motivated me to continue to write. And the more I wrote, the better I felt. And when I finally got to the end of the book, I had healed in a way. And I mean, you don’t really just heal all together, but it was a sense of release.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.